Guest Post: David F Ross

Today I am pleased to welcome David F Ross.

Today I am pleased to welcome David F Ross.

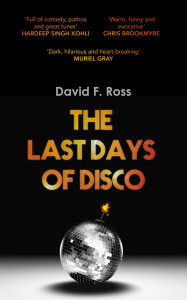

As part of the Blog Tour to celebrate the paperback launch of his exceptional novel The Last Days of Disco, David has kindly shared some recollections of his early musical influences.

The Thin White Duke Street

The Last Days of Disco is very nostalgic and much of that comes from the music of that time in the early 80s. There’s nothing else quite like a piece of music to pin-point a significant memory. From first days at school, to loss of virginity (one of these days I’ll finally remember where I left it…) to the birth of my children; all of the vivid moments in my life – good and bad – have had an associated soundtrack. Like the majority of you reading this, I suspect, music has an importance to me that’s often found bordering on the irrational.

From the eight years before 1972 that I knew her, my only remaining recollections of my mum involve music. Although not through the beat groups of the early and mid-sixties, surprisingly. My dad was a country and western fan, particularly of Johnny Cash and Merle Haggard. Their subliminal influence has left me with a natural tendency towards songs with a darkly descriptive background story. Glen Campbell was also a favourite of both my parents, as were the crooners. Sinatra, Crosby, Como and Martin were all regularly played on the big mahogany Marconi radiogram that competed for their attention in the opposite corner of the living room from its main rival, the black and white television set. Their records were the backdrop to my early years in the small fourth floor, brownstone top corner tenement flat where we lived, near Hampden Park on Glasgow’s Southside.

My dad especially, acquired lots of diverse records from various sources. The LP and singles covers for many of them are as vivid to me now as they were then. Old Blue Eyes, smiling, hair receding, calm and confident from the sleeve of ‘My Way’. ‘Little Old Wine Drinker Me’ with its Reprise logo in black on a black and white portrait of Dean below the heading ‘File Under Easy Listening’. Johnny’s gravity defying, brylcreem supported quiff with an attitude all of its own, live from ‘Folsom Prison’. The big red lipstick kiss on the cover of Connie Francis’ most famous record. Don and Phil Everly’s pearly white teeth and matching checked Arthur Montford jackets concealing the then little known fact that they despised each other. The Zombies brilliant and beautiful ‘Odessey & Oracle’, which remains one of my all-time favourite LPs. These records were the foundation for my interest in music and for this legacy at least, I am thankful to my dad. I loved these songs and still do but I inherited them. They’re not mine and the recollections that they prompt now often seem to belong to someone else.

My grampa had taken the death of his youngest child particularly badly. Despite their frequent, but generally good-natured arguments, they were very close. He’d lost weight and had suffered a minor stroke in the immediate aftermath of the funeral and it had forced him to retire. He also had a genuine fondness for my dad. Both worked in the transport industry; my dad for British Rail and his father-in-law latterly for Glasgow Corporation as a bus conductor on a regular route along Duke Street. An agreement had been reached where my grieving dad and I were to stay with his in-laws, partly to give the old man something to focus on but more practically because there really was no other viable option. My other grandparents were older, infirm and lived in a relatively small second floor flat in Tollcross.

Pollok was, and undoubtedly still is, an impoverished working-class enclave south west of the Clyde. My gran frequently lamented that it was home, very briefly, to Moors Murderer Ian Brady, but she had it mixed up with the more upmarket Pollokshaws. The house in Pollok was a three-bed-roomed one. It sat opposite the bus stop at the bottom of the hill on Braidcraft Road. My grampa was a keen gardener and the reasonably sized rectangular garden at the back of the house was a testament to his hobby. I loved the house. There were loads of places to hide and, with the garden I had a ready made football pitch and a net in the form of a five-foot-square wire plant climber. The flat we’d previously lived in had a shared drying green but no grass. There was always loose rubbish congregating around the concrete ‘middens’, and as a result, a large and uninhibited rodent population flourished.

My grampa was very proud of his garden. He spent hours in his small greenhouse at the bottom of the garden where he grew tomatoes. The greenhouse sat just behind the impromptu football net and on a few occasions, a fierce thirty yard shot from Derek Parlane went past the imaginary Evan Williams, bursting the net, and unfortunately the greenhouse glass. Each time my excuse was the same. A big boy did it and ran away. He’d thrown a stone from Levernside Road and it broke the glass. My grampa indulged this fantasy every time despite the fact that to the glass from Levernside Road would require an aim and trajectory ranking alongside the Magic Bullet Theory.

‘Starman’ was the first record I bought with money that could be considered my own. There’s my plea for coolness. My grampa had paid me for cutting his beloved grass with an old manual blade lawnmower. I made a terrible, patchy job of it but he kept his side of the deal anyway. But perhaps more accurately, the first record I was given was by a band named the Strawbs. The a-side was titled ‘Part of the Union’ but I quickly grew to hate it as it jumped at the start of the chorus. Years later I heard the song again and I fully expected it to go:

‘You don’t get me; I’m part of the U…part of the U…part of the U…part of the U…’ for days until someone eventually lifted the needle. At the age of eight, I blamed the record for its inability to get to the end of its grooves. I’d no idea that a blunt stylus was the real culprit. The bastards could sing it fine on the radio. Why did they only get the stutters in my grampa’s house? I’ve tried to excise this blundering, stammering shambles from my personal history, but it’s still there, at the back, hand up, protesting like a belligerent old shop steward.

‘You don’t get me; I’m part of the U…part of the U…part of the U…part of the U…’ for days until someone eventually lifted the needle. At the age of eight, I blamed the record for its inability to get to the end of its grooves. I’d no idea that a blunt stylus was the real culprit. The bastards could sing it fine on the radio. Why did they only get the stutters in my grampa’s house? I’ve tried to excise this blundering, stammering shambles from my personal history, but it’s still there, at the back, hand up, protesting like a belligerent old shop steward.

‘David Bowie can get tae fuck, boy. Ah wis yer f…f…f…f…f…first.’

The image of David Bowie on Top of The Pops in the summer of ’72 was revelatory. My grampa wasn’t impressed but I was astonished. Years later, people would debate whether Boy George was male or female, but watching him then, Bowie didn’t even seem to be from the same species as me. I knew instantly where my ‘wages’ were going. The Bowie record had a green and white plain sleeve with, to my initial but short-lived dejection, no picture. The famous orange RCA label glowed through the circular cut out. Despite its aesthetic shortcomings, I came to think of it as a thing of beauty. I got it on a trip into Glasgow from Woolworth’s on Argyle Street but a different store from the one that had been there until the chain became extinct in the worldwide fall-out from the American sub prime credit crisis. It cost 24 new pence. Jim Murdoch and Ally Baxter were with me when I got it. Both were a couple of years older than me. Jim’s dad had taken us all into the city. I remember the two of them laughing because I’d bought a record ‘by a fuckin’ poofy cunt’. When I got back home, the two others went out to the back garden and were dummy fighting with each other. But I sat in the living room, silently staring at the big wooden box as Bowie’s voice came out of the speakers. To my utter delight, it did so without any speech impediment.

I idolised my grampa. He told brilliant stories. Ones where even years later as a young adult, I firmly believed he was right despite the obvious scientific or logical arguments against some of his more ridiculous ones. Once, when I was about nine years old, I asked him how colour TV worked, he told me that it wasn’t actually new technology. His explanation was that since the end of the Second World War, life was in fact monochrome. His explanation for this was that the Government was so taken aback by the euphoric reaction to the war ending that it became concerned that the years of struggling and post war rationing that would follow would be too much to bear. The Government then gave everyone injections that removed the colour from their skin and hair. After a period of time, people became so accustomed to the lack of colour that building materials became monochromatic, colourless foods like semolina predominated and television shows like the Black and White Minstrels emerged to reflect society’s disinterest with anything from the spectrum. TV, he argued with the conviction of a Nobel Prize winning scientist, simply reflected a more disheartened Age. Then flower-power came along and the people demanded their colour back so that the flora and fauna could be fully appreciated again. I used to sit open-mouthed when he told stories like this. My head would nod at bits where my own experience could back up the theory.

‘Semolina, you say…? Jesus, he’s right…! There’s a ton of that at our school.’

Another yarn was that air flight didn’t actually happen. You got on a plane, and while on it, teams of trained experts changed the surroundings outside. The plane didn’t actually go anywhere. The more dramatic the change in scenery, the longer you had to sit on the plane. I assumed that he meant that if you wanted to go to Africa, you had to sit on the tarmac for around 15 hours until the ‘crew’ had rounded up enough black people, safari animals and weird looking trees. Since I hadn’t been on a plane at this point, I’d no reason to question the wisdom of this old sage. Forty years later and I’m writing this now on a long haul flight back home from Singapore and a part of me still needs convincing that I’m not actually on a simulator.

I lived with my grandparents for three years before another move and a new phase of life began in Ayrshire. On the night before we left their house for good, the old man told me he had something for me. I sat expectantly, waiting for him downstairs while he disappeared upstairs for what seemed like an hour. When he returned, it was with a face whitened by talcum powder and with a shaky red lipstick flash drawn down his face. In his hand was the Aladdin Sane LP.

‘Mibbe ah wis wrang aboot this yin, aw along. He’s actually awright, son’.

I remember laughing so much, I pee’d myself. I can’t look at the LP’s sleeve now (or actually Heath Ledger’s ‘Joker’ in the Dark Knight Rises, such was the botched make-up job…) without seeing old James Fleming’s smiling face.

David Bowie and my grampa; The Thin White Duke Street. Heroes.

The Last Days of Disco by David F Ross is published by Orenda Books and is available in paperback and digital format now. My review (score 5/5) can be found here: https://grabthisbook.net/?p=437

The Last Days of Disco by David F Ross is published by Orenda Books and is available in paperback and digital format now. My review (score 5/5) can be found here: https://grabthisbook.net/?p=437