Decades: Compiling the Ultimate Library with Jo Perry

There is a LOT of reading to follow as Jo Perry joins me to take on my Decades challenge so I shall be brief.

I am compiling the Ultimate Library, each week I am joined by a guest who helps me curate my Library. My guests are all asked to nominate ANY five books which were published over five consecutive decades.

This week I am thrilled to be joined by Jo Perry. Jo’s Charlie and Rose books are big favourites at Grab This Book. I didn’t know how the story of a dead man and a dead dog could captivate me or even how it could work! Four books later I am utterly charmed, thrilled and heartbroken by the unlikely duo’s exploits. I could not wait to see which books Jo would nominate, I most certainly did not expect an author from Los Angeles to pick a book which featured my Scottish hometown of Airdrie!

Jo Perry earned a Ph.D. in English, taught college literature and writing, produced and wrote episodic television,

Jo Perry earned a Ph.D. in English, taught college literature and writing, produced and wrote episodic television,

and has published articles, book reviews, and poetry.

She lives in Los Angeles with her husband, novelist Thomas Perry.

They have two adult children. Their three cats and two dogs are rescues.

You can follow her on twitter @JoPerryAuthor

Jo has five books published by Fahrenheit Press: Dead is Better, Dead is Best, Dead is Good, Dead is Beautiful and her latest: Pure. You can buy directly from Fahrenheit’s website: http://www.fahrenheit-press.com/authors_jo_perry.html

DECADES

Compiling a list of the books most important to one’s intellectual, emotional or writing life would be a difficult task, but to be confined to five books from five consecutive decades is impossible. This cruel game forbids me from including books like Richard Brautigan’s Trout Fishing in America. But its Fred Astaire grace, its narrative-as-standup, its poignant, haiku’d prose, the slippery delight it takes in its own slyness and shyness, its literary rule-smashing, the exuberant fecundity and clarity of its metaphors, its benevolent voice and radioactive-with-meaning mayonnaise-white spaces on its pages were my first experience of what artistic freedom can produce and the courage and grace required to seize it. But since I’m sworn to abide by the rules of the Decades exercise, I will omit Trout Fishing in America, a representative of a decade I cannot include. Forget I ever mentioned it.

Clarissa, Or The History Of A Young Lady by Samuel Richardson

When I wrote my doctoral dissertation on Richardson in 80’s, I was no longer the reader who’d fallen hard for Trout Fishing in America. I wasn’t seventeen and greedy for influence, though I still wanted books to illuminate me to the point of ignition and “to [make me] feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off”—which is how Emily Dickinson described what poetry—real poetry––made her feel.

When I wrote my doctoral dissertation on Richardson in 80’s, I was no longer the reader who’d fallen hard for Trout Fishing in America. I wasn’t seventeen and greedy for influence, though I still wanted books to illuminate me to the point of ignition and “to [make me] feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off”—which is how Emily Dickinson described what poetry—real poetry––made her feel.

Richardson’s improbable, alchemical masterpiece (improbable because his biography and earlier work revealed none of the ambition, gravitas, or power of Clarissa) burns slowly because it’s long–the longest novel in the English language. And it’s the longest novel in English because it unfolds through letters from Clarissa to her closest friend, and from John Lovelace, the man who would possess Clarissa, to his friend. The plot is simple: Clarissa’s mercenary family maneuvers her into agreeing to marry a toad because the union will benefit them financially. Clarissa knows that the marriage, a dehumanizing transaction, will destroy her life. Lovelace manipulates Clarissa into running away with a promise of protection, then proceeds to ruin her. She dies, her soul and her self intact. Clarissa is a feminist tragedy, a class-novel, and a rape and disempowerment and transcendence novel. The abridged version you’ll find is just plot. A rich, powerful predator entrapping a woman disempowered by society was a story Richardson had already written in Pamela, the virtue-rewarded happy-ending version of this tale and also the first novel in English. Clarissa’s epistolary form immerses the reader in each character’s first-person voice, point of view and experience. These first-person narratives power a deliberate, intense, inevitable build-up to, and unfolding of a catastrophe in epistolary time, not glib narrator-time. The effect is grandeur.

Dance for the Dead by Thomas Perry

“The Old People believed that the place to obtain secret information was in dreams. Sometimes a dream would be an expression of an unconscious desire of the soul, and at other times a message planted there by a guardian spirit. Those were two ways of saying the same thing. If there were such a force as the supernatural, then the soul and the guardian both would be supernatural. If there were no such force, then the soul was the psyche, and the guardian spirit was just the lonely mind’s imaginary friend.”

“’I hear you’re one of those people who could kill me with a pencil,’ he says. Jane answers simply: ‘If I am, I wouldn’t need a pencil.’”

During the 90’s I was mostly reading Babar and the Boxcar Children, childcare books and my husband’s novels, which I’d been reading since he wrote The Butcher’s Boy (1982). During the new decade he created Jane Whitefield, a contemporary, mixed-race (Seneca and white) woman who lives in a town very much like the town where he grew up in western New York. Jane Whitefield is a guide; she helps people in danger disappear and teaches them how to inhabit the new identities she invents for them. Dance for the Dead, the second in the series, has always stuck with me. Being inside Jane’s head showed me how easily the person we think we are can be disappeared, and transformed my sense of the world––there are many more opportunities for violence, betrayal and hurt than I’d imagined; past and present are contemporaneous and this simultaneity can be realized with crystalline precision and emotion on the page. Jane Whitefield is heroic, but she makes mistakes. This second book is where Jane crossed over from fiction to being someone real and important to me.

The Sociopath Next Door by Martha Stout

“A part of a healthy conscience is being able to confront consciencelessness. When you teach your daughter, explicitly or by passive rejection, that she must ignore her outrage, that she must be kind and accepting to the point of not defending herself or other people, that she must not rock the boat for any reason, you are NOT strengthening her prosocial sense, you are damaging it–and the first person she will stop protecting is herself.”

“’I saw a werewolf drinking a pina colada at Trader Vic’s. His hair was perfect.’”

Yes, Stout quotes Warren Zevon’s “Werewolves of London,” maybe my favorite song.

Parenting means constant worrying about your child’s wellbeing and safety. Maybe that’s why The Sociopath Next Door by Martha Stout was so clarifying. A few of the things that were revelatory to me: The sociopath is invisible. The sociopath relies on our best qualities to exploit us: our kindness, generosity, empathy, the qualities the sociopath lacks and depends on us to stifle gut-feelings of fear or revulsion or that something is off with him. And we can’t avoid the sociopath. He or she is a permanent member of the human family. One in twenty-five people––ordinary, usually not violent, not usually criminal masterminds, often pleasant or charming––doctors, friends, teachers, caregivers of our children and our aging parents, neighbors, pastors, rabbis, roommates, bosses or colleagues, best friends––will fuck us over every chance he or she gets––usually with our help and tacit permission––and will probably know how to make us feel guilty enough when you catch them at it to do it again.

There are more elegant nonfiction books that I’d add to this list if I could: Brilliant: The Evolution of Artificial Light by Jane Brox changed the way I read literature; Through the Language Glass by Guy Deutscher––reveals so much about language and color and why Homer said “wine-dark” sea and not “blue.” Timothy Egan’s elegiac biography of Edward Curtis, Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher––but Stout gets the modus operandi of this perfectly selfish predator, most efficient opportunist, manipulator and emotional assaulter down.

Mortality by Christopher Hitchens

“In one way, I suppose, I have been ‘in denial’ for some time, knowingly burning the candle at both ends and finding that it often gives a lovely light. But for precisely that reason, I can’t see myself smiting my brow with shock or hear myself whining about how it’s all so unfair: I have been taunting the Reaper into taking a free scythe in my direction and have now succumbed to something so predictable and banal that it bores even me.”

“In one way, I suppose, I have been ‘in denial’ for some time, knowingly burning the candle at both ends and finding that it often gives a lovely light. But for precisely that reason, I can’t see myself smiting my brow with shock or hear myself whining about how it’s all so unfair: I have been taunting the Reaper into taking a free scythe in my direction and have now succumbed to something so predictable and banal that it bores even me.”

“I don’t have a body, I am a body.”

“The most satisfying compliment a reader can pay is to tell me that he or she feels personally addressed. Think of your own favorite authors and see if that isn’t precisely one of the things that engages you, often at first without your noticing it. A good conversation is the only human equivalent: the realizing that decent points are being made and understood, that irony is in play, and elaboration, and that a dull or obvious remark would be almost physically hurtful. This is how philosophy evolved in the symposium, before philosophy was written down. And poetry began with the voice as its only player and the ear as its only recorder.”

If something is worth hearing or listening to, it’s very probably worth reading. So, this above all: Find your own voice.”

“With infinite life comes an infinite list of relatives. Grandparents never die, nor do great-grandparents, great-aunts … and so on, back through the generations, all alive and offering advice. Sons never escape from the shadows of their fathers. Nor do daughters of their mothers. No one ever comes into his own … Such is the cost of immortality. No person is whole. No person is free.”

I arrived in my 6th decade and became interested in death and, I see now that I was also unconsciously working up to and researching for my first novel, Dead Is Better. I’d read other books on the topic, but Christopher Hitchens’ posthumously collected writings produced while he was dying of esophageal cancer––which killed his father and my grandmother––besides confirming that dying is a bitch––cruel, thieving, humiliating, disabling––is informative, funny, heartbreaking set-your-hair-on-fire enlightening, and heartening, a whatever life one has left-invigorating demo that that sharp thinking produces sharp writing, that sharp thinking requires courage, and that a writer’s relationship to his reader (imagined or real) is incredibly intimate and requires––if it’s going to go all the way––naked honesty––and that writing is a conversation like the ones Hitchens describes with friends as having been among the greatest pleasures of his too-short time on earth.

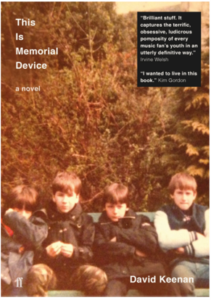

This Is Memorial Device by David Keenan

“Lucas was building a volcano in the middle of his caravan. The volcano, he explained, was the equivalent of a wheelchair for a physically handicapped person. It’s a means of transport, he said. It allows me to make connections. The volcano was constructed out of old shoeboxes, crumpled newspapers, folded greeting cards, balls of wrapping paper. Long feather boas – pink, blue and purple – took the place of flowing lava… …I have struggled with mental illness for most of my life. But the creative part, the creative part has been the most rewarding. He spoke in a soft, slightly distant voice. A moonie, I thought to myself, a gentle lunatic.

“Lucas was building a volcano in the middle of his caravan. The volcano, he explained, was the equivalent of a wheelchair for a physically handicapped person. It’s a means of transport, he said. It allows me to make connections. The volcano was constructed out of old shoeboxes, crumpled newspapers, folded greeting cards, balls of wrapping paper. Long feather boas – pink, blue and purple – took the place of flowing lava… …I have struggled with mental illness for most of my life. But the creative part, the creative part has been the most rewarding. He spoke in a soft, slightly distant voice. A moonie, I thought to myself, a gentle lunatic.

The issue was memory. He had none, or very little, or rather all of his memories were hidden, occluded by chemistry, by water particularly – water on the brain they called it – so that every moment was swept away, the specifics of his day-to-day existence like the splinters of a ship in a storm. This is the logbook, he said, thumbing through notes, moments reconstructed in the wake of a disaster. Then he pointed to the volcano. And this is where the memories live…”

“I don’t know. They were leafing through it one night and he turns to a page that has a picture of Elvis on it. Early Elvis. Young Elvis. Elvis where he looks like a flick knife. And just looking at him he feels like he has stuck his finger in a light bulb socket. He says he literally felt his hair rise up into a kind of electrified quaff. And you know what he means. That haircut was aerodynamic. It came from rushing headlong into the future. He asked his friend, who the fuck is this guy? And he says to him, it’s the new singer. But he mishears it as It’s Sinew Singer and his mind is even more blown apart. He mishears it and this guy whose every muscle, whose every vein, every fucking sinew of this body is singing, you know? Fuck Iggy Pop! And then he realizes his mistake though not really because in that moment he became Sinew Singer. He took on the mantle and it was down to him to live up to it. That’s genius right there, if you ask me. In my opinion genius is accidental, is mistaken, is actually wrong at first. And I don’t care what you say. But it’s hard to be wrong in a housing estate in Airdrie. Even though really they’re all wrong! But they want to be right at all costs. They want to have an ironing board, a cooker and a washing machine. A duvet instead of a sleeping bag. A fucking concrete house with four windows. Some shitty car. A hoover. A job like a fucking jail sentence. A bit TV in the living room. To be woken at six in the morning while it’s still dark. And on top of that they want respect. For being right. How is it possible to respect anyone for being right?

?

How fucking simple. How mind-numbingly fucking dull. Congratulations, You did the right thing. You know?…”

“…I think there is something fulfilling for Lucas and for all of us in being able to make ritual use of forgetting and remembering. And of course that’s how I came up with the name Memorial Device. To me it was like Shakespeare…”

“I’m drawn to madness… I admit it… but only if it energises you… or if it destroys you completely… Only if you blow up or go tearing off… into another life… and another life… and another life running after it…”

This Is Memorial Device by David Keenan. I am squeezing it into the current decade although I may have read it on the cusp. It’s a fictional memoir about what Amazon.com calls “the post punk scene” in Airdrie, a working-class town in Scotland. I read it as research for a character who is the hero of the book I am working on now who is based on a real person who is also a hero. Anyway, This Is Memorial Device is a novel about rock music built as a series of interviews about a band called “This Is Memorial Device.” The voices transcribed in the interviews are electric currents that crack stuff open like hammers against geodes. If there’s a connection between all the books on this list it’s that they are products of empathy and don’t congratulate themselves for following formulae or achieving a recognizable, conformist aesthetic. They’re poetry.

My thanks to Jo for these amazing selections. My invitations to participate in Decades highlight that the book selection is a very personal choice. Having five books which were each read in five different decades of Jo’s life is indeed a very personal selection and falls within “flexing” of the Decades rules